Introduction

‘Contemporary LGBT abuse literature does not simply construct the way in which we understand this issue but also, and perhaps more importantly, it determines and limits…what can be seen, heard, thought, known and done about it’ (Kwong Lai Poon, 2002:19)

Domestic abuse is a problem that cuts across a cross-section of society, although evidence shows that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) victims are disproportionately affected (Ristock, 2011). The longstanding narrative around domestic abuse has long since been heteronormative, due to ‘heterosexual hegemony’, and second wave feminist literature which portrays domestic abuse as gendered with men primarily being the perpetrators and females being the victims (Donovan & Hester, 2014). It has thus been difficult for survivors and society alike to acknowledge and situate the experiences of LGBT people as domestic abuse (Donovan & Hester, 2014; Monckton-Smith et al, 2014). This literature review seeks to examine the prevalence of domestic abuse in LGBT relationships; the explanations for the abuse and suggest ways in which the problem can be tackled. .

2.0 The Extent of the Problem

We currently have a very limited picture of the domestic abuse problem in the LGBT community as obtaining accurate prevalence data is problematic for a number of reasons. Firstly, despite widely available statistics on domestic abuse in the UK, there are no official figures on the prevalence of domestic abuse in those identifying themselves as LGBTQ. Secondly, domestic abuse is widely underreported within the LGBTQ community and research suggests that rates of under-reporting within the LGBTQ population are between 60-80% (Galop, 2020) which is consistent with the national underreporting rate of 79% according to the Office for National Statistics (2018). Safelives (2019:9)’s national datasets found that ’just 2.5% of people accessing support from Insights domestic abuse services identified as LGBTQ’.

There have been a few empirical studies conducted on the rates of domestic abuse in the LGBTQ community. One such study by Donovan et al (2014: 7) showed that 38.4% of the 692 respondents had experienced domestic abuse at some point in their lives, and these statistics are comparable to the figure of 40% from Henderson’s (2003) study. Moreover, according to Donovan et al (2014:7), 40% of the female respondents and 35.2% of the male respondents reported being victims of domestic abuse. It has thus been reported by some studies that gay men are less likely to report or recognise domestic abuse compared to lesbian or bisexual women (Donovan et al, 2014). Contrastingly, Henderson’s (2003) research with over 1000 participants showed that 22% of the women in the study had experienced domestic abuse compared to 29% of men. Similarly, Stonewall’s (2008-2011) 25% of lesbian and bisexual women have experienced domestic abuse in a relationship and almost half (49%) of all gay and bisexual men have experienced at least one incident of domestic abuse from a family member or partner since the age of 16(Galop, 2018 :6).

The discrepancies in data have been attributed to methodological inconsistencies such as varying sample sizes and different definitions of domestic abuse for lesbian and gay participants (Kelly, 1997). Kelly (1997) argues that lesbian respondents are more likely to identify abusive behaviours due to the feminist movement which brought violence against women to the forefront. Kelly (1997) also argues that surveys with lesbian and bisexual women define domestic abuse more broadly than for gay men and this is supported by Hester & Donovan’s (2014) qualitative interviews with a sample of lesbians and gay men. On the contrary, Stonewall’s (2008-2011) study included familial violence in their definition of domestic abuse for gay men but not for lesbian or bisexual women, which could explain the higher proportion of gay victims of domestic abuse.

What is consistent within literature is that rates of domestic abuse are estimated to be higher for those identifying as transgender (Galop, 2019; Scottish Trans Alliance, 2010). According to the Scottish Trans Alliance (2010:6), 80% of transgender victims in their study had experienced domestic abuse. A systematic review of literature by Peitzmeier et al (2019:2378) found that transgender individuals are 2.2 times more likely to experience physical abuse and 2.9 times more likely to experience sexual abuse than are cisgender individuals. Transgender victims experience abuse disproportionately and more remarkably than cisgender individuals and they are at a higher risk of repeat victimisation (Peitzmer et al, 2019). Peitzmer et al (2019) argue that experiencing transphobia as well as domestic abuse can result in very severe mental health issues for the transgender community. More broadly, rates of mental health issues and complex needs are higher for LGBT people than for their heterosexual counterparts (Galop; 2019; Safelives, 2019). Safelives (2019:26) reported that 51% of LGBT survivors accessing support services were experiencing mental health issues compared to a rate of 38% for the heterosexual, cisgender survivors.

Literature has shown that the types of abuse were heterogeneous across the LGBT community. Gay men were reported to be more likely to experience physical abuse and bisexual women were at the most risk of sexual abuse throughout their lifetime (Galop, 2019; Donavan et al, 2014). ‘In comparison, lesbian women disclosed the highest levels of financial abuse, which was disproportionate compared to bisexual victims/survivors’ (Galop, 2018:16). According to Galop (2018:16), ‘trans women disclosed disproportionately higher levels of physical, sexual and financial abuse compared to trans men, who disclosed higher levels of harassment/stalking and verbal and emotional abuse.’

Prepared by Stacey Musimbe-Rix for the KSS CRC Research and Policy Unit

3.0 Understanding the Nature of Domestic Abuse in LGBT Relationships

Limited research has been conducted which seeks explanations beyond the heterosexist understandings of domestic abuse. Explanations are important as they help us understand the perpetrators and therefore develop appropriate responses. The explanations for LGBTQ domestic abuse can be broadly separated into individualistic and societal factors (Donovan & Barnes, 2017).

One of the individual theories offered for LGBT domestic abuse is the ‘disempowerment theory.’ Disempowerment theory suggests that individual factors such as self-esteem, personality, family of origin and insecure attachment can make a person more prone to abusing their partner (Mendoza, 2011). The acts of domestic abuse are therefore seen as an individual’s reassertion of dominance when they feel out of control. According to this theory, other individual factors which are purported to make an individual susceptible to violence include mental health and substance misuse. (Kwong-Lai Poon, 2011).

This disempowerment theory is problematic as it goes against traditional understandings of domestic abuse by theorists such as Dobash & Dobash (1998), who show that such individual factors might be a catalyst but not a causal factor for domestic abuse (Donovan & Hester, 2014). Kwong-Lai Poon (2011) challenges such theories and argues that there is no scientific evidence to prove that mental illness and substance misuse cause domestic abuse. Furthermore, Donovan & Barnes (2017) argue that significant rates of mental illness and substance misuse can also be found in heterosexual communities and in victims, therefore such theories do not offer a reliable explanation for domestic abuse specific to LGBT communities.

Developing on disempowerment theory; minority stress has been theorised as one of the reasons that domestic abuse occurs within the LGBTQ community. Minority stress ‘has been defined as experiencing psychological and social stresses that arise from one’s minority status (i.e., stigmatization), and the discrimination associated with it’ (Mendoza, 2011:170). A few studies have asserted that there is a positive correlation between minority stress and domestic abuse (Mendoza, 2011; Meyer, 2001). Mendoza (2011) hypothesised that internalized homophobia, stigma and prejudice in gay participants interact and lead to the perpetration of physical violence against a partner. Other theorists such as Donovan & Hester (2011) disagree with this theory and instead they suggest that minority stress can be used to explain a lack of help seeking within the LGBTQ community and not the abuse. They argue that external homophobia and prejudice can often pose as a barrier to accessing support for those within the LGBTQ community and it can compound the effects of the abusive behaviour (Donovan &Hester, 2011).

Donovan & Hester (2011) instead argue that heteronormative understandings of domestic abuse can still be applied to LGBTQ relationships i.e. mutually violent control, common couple violence, intimate terrorism and violent resistance (Johnson, 2006), although the abuse should be looked at through an intersectional lens. While these theories can be applied to LGBT relationships, it is important to note that the added layer of complication that comes from belonging to the LGBT community mediates their experiences. LGBT victims of domestic abuse consequently experience domestic abuse differently to heterosexual cisgender communities. Furthermore individual LGBT experiences of domestic abuse are shaped by other intersecting oppressions such as race, class and disability. According to Kwong-Lai Poon (2011:124):

‘We need to explore how the experience of violence is mediated, not only through homophobia and hetero-sexism, but also through privilege (whiteness) and other forms of oppression; how meanings of violence, power, control, agency, strength, and resiliency intersect with social dimensions such as race, gender, class, disability, and sexual orientation within relationships.’

Illustrative of this, Stonewall (2018:5) found that 51% of those from a Black or Minority Ethnic (BME) background experienced discrimination within their community due to their race and 36% of transgender survivors experienced discrimination within the LGBT community.

Despite a wide range of literature, an evidence gap still exists on the reasons for domestic abuse within the LGBT community and, this warrants further research which would help us develop a fuller understanding of LGBT perpetrators and thereby develop targeted interventions.

4.0 Responding to Domestic Abuse

Considering the extent of the problem, it is important to look at how society and professionals can respond and address the issue appropriately. Responding appropriately is crucial in the safeguarding of LGBTQ survivors of domestic abuse. Public narratives often shape the way in which an individual from the community frames their story (Donovan & Hester, 2014). Literature therefore highlights the importance of more concerted efforts to include LGBT victims into the public narrative thus going beyond the heteronormative framework (Stonewall; 2018).

One way to do this is to develop campaigns and materials which are LGBT specific and that clients can identify with (Donovan & Hester, 2014; Donovan & Barnes, 2017; Stonewall, 2018). There have been tireless efforts by third sector organisations such as Galop in order to bring the issue of LGBT abuse to the forefront, however literature reiterates that these efforts need to be made more mainstream. Within offices and office buildings, it is important that posters, leaflets and other materials are issued which highlight domestic abuse within the LGBT community as a problem. In order not to be tokenistic, these efforts need to be made all year round and not just during events such as pride.

The most cited barrier to accessing support for the LGBT community is a distrust of services due to pervasive experiences of homophobia and transphobia (Stonewall, 2018; Donovan & Hester, 2014). According to the National LGBT Survey (2018:17), ‘21% of Trans respondents said their specific needs were ignored or not taken into account when they accessed, or tried to access, healthcare services in the 12 months preceding the survey.18% said they were subject to inappropriate curiosity and 18% also said they avoided treatment for fear of discrimination or intolerant reactions’.

It is therefore important that services including the criminal justice agencies are accessible and inclusive. In addition to developing LGBT specific materials, initiatives such as LBGT reporting times; collaborative working with LGBT organisations; LGBT service user councils and LGBT representation within organisations can help to break down the barriers and make services more inclusive (Harvey et al, 2014). It is important that in creating LGBT inclusive services, intersecting identities of the survivors are also taken into account, as this might make a victim more vulnerable (Stonewall,2018; Kwang-Lai Poon, 2011). It is important, therefore that the often complex needs of LGBT clients are recognised in service delivery models.

Another widely identified gap within the criminal justice system is a lack of domestic abuse perpetrator programmes for LGBT people (Safelives, 2018). Although LGBT perpetrators receive one to one support to tackle their abusive behaviours, evidence suggests that group work could be more effective (Stonewall & NFP Energy, 2018). Evidence shows that there is an overwhelming need for tailor made perpetrator programmes.

Literature has also shown that some professionals have very little understanding of domestic abuse within the LGBT community (Stonewall & NFP Energy, 2018) and this results in prejudice, stereotyping and inappropriate responses. It is therefore important that those working on the front line with LGBT service users receive training and are upskilled to work appropriately with LGBT service users. Resources are now widely available such as Safelives’ guidance on specific abuse unique to LGBT relationships:

- Threat of disclosure of sexual orientation and gender identity to family, friends, or work colleagues

- Increased isolation because of factors like lack of family support or safety nets.

Undermining someone’s sense of gender or sexual identity particularly when one partner is transgender - Limiting or controlling access to spaces and networks relevant to coming out and coming to terms with gender and sexual identity

- The abused may believe they ‘deserve’ the abuse because of internalized negative beliefs about themselves

- The abused may believe that no help is available due to experienced or perceived homo/bi/ transphobia of support services and the criminal justice system.

(Galop, 2020:2)

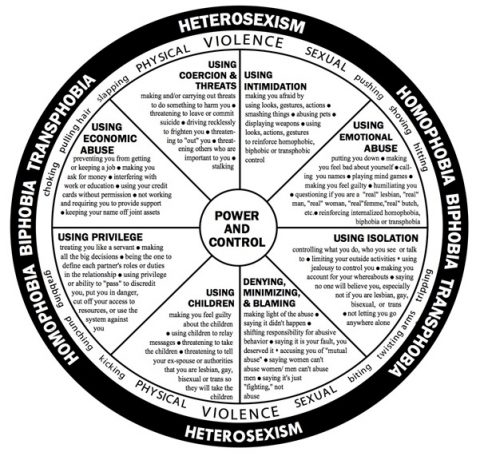

Other resources which have been developed include the LGBT Power and Control wheel which can be used by LGBT victims and perpetrators of domestic abuse.

LGBT Power and Control Wheel

Roe and Jagdonski (no date) adapted from Power, Control and Equity Wheels developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project, Duluth, Minnesota

Evidence suggests that there is still a lot to be done to build trust between professionals and the LGBT community, particularly those from the transgender community (Donovan & Hester, 2014; Galop, 2018; Scottish Trans-Alliance, 2018). LGBT survivors of abuse face individual, interpersonal, structural and cultural barriers when attempting to access services (Harvey et al, 2014). The barriers are even more acute for transgender individuals who are the most marginalised within the LGBT community.

Accessing services for trans women can be particularly re-traumatizing and triggering and this needs to be considered when attempting to engage them. Many women’s only spaces (including refuges) are inaccessible for trans women due to the policies of the organisations, or oftentimes trans women do not feel safe due to the hostility from staff and other service users (Safelives, 2018; Harvey et al, 2014.). One suggestion from professionals in Stonewall & NPF energy’s (2018) study is that transgender people need to do more campaigning in the same way than many gay and lesbian people campaigned for visibility within services. However, this narrative is unsettling as the transgender community is particularly vulnerable and marginalised and adding the emotional labour of educating the population would compound the difficulties that the community already faces. Creating a safer community should arguably be the burden for us all.

3. Conclusion

Research has shown that domestic abuse within the LGBT community is a widespread problem and more so than in the heterosexual community. The lack of visibility is likely due to underreporting and not due to a lack of abuse (Galop, 2019). Rates of underreporting show us that many LGBT survivors do not feel safe or able to identify their experiences as abusive due to the ‘heterosexual hegemony.’ We therefore need to change the narrative around domestic abuse to actively include LGBT survivors and this also includes putting measures in places such as training for staff, LGBT councils and campaigns. The review of literature also suggests that despite the prevalence of abuse within this community, the experiences of abuse are not homogenous and these are compounded by factors such as class, race and disability. Within the LGBT community, transgender individuals continue to experience abuse disproportionately and face the most barriers to getting help compared to others within the community. BME victims have also been shown to be under served within these communities which begs the question of tailored support for those facing more than one form of oppression. Despite a wide range of research, an evidence gap still exists and more research is needed into domestic abuse within the LGBT community, as research informs prevention and response policies (Galop, 2010; Waldner-Haugrud, 1997).

Stacey Musimbe-Rix – Probation Practice Researcher

KSS CRC Research and Policy Unit

April 2020

References

Domestic Abuse in Same Sex and Heterosexual Relationships. Last accessed 15 April 2020.

Donovan, C. ,Barnes, R. and Nixon, C. (2014) The Coral Project: Exploring Abusive Behaviours in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and/ or Transgender Relationships: [online]. Last accessed 3 April 2020.

Donovan, C and Hester, M. (2014) Domestic Violence and Sexuality: What’s Love Got to Do with It? Policy Press, 2014. Online Resource.

Harvey, M. Mitchell, J. Keeble, C. McNaughton Nicholls, and N. Rahim,

Barriers Faced by Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People in Accessing Domestic Abuse, Stalking and Harassment, and Sexual Violence Services. Cardiff: Nat Cen Social Research, 2014.

Haugrud-Waldner, L., Vaden-Gratch, L. and Magruder, B. (1997) Victimization and Perpetration Rates of Violence in Gay and Lesbian Relationships: Gender Issues Explored, Violence and Victims 12(2).

Henderson, L. (2003) Prevalence of domestic violence among lesbians & gay men. Last accessed 3 April 2020.

Kwong-Lai Poon, M. (2011) Beyond Good and Evil: The social construction of violence in intimate gay relationships in Ristock, J. (2011) ‘Introduction: Intimate Partner Violence in LGBTQ Lives’. Routledge. Online Resource.

Magić, J. & Kelley, P. for Safelives (2018). LGBT+ people’s experiences of domestic abuse: a report on Galop’s domestic abuse advocacy service. London: Galop, the LGBT+ anti-violence charity.

Magić, J. & Kelley, P for Safelives. (2019). Recognise & Respond:

Strengthening advocacy for LGBT+ survivors of domestic abuse. Galop, the LGBT+ anti-violence charity.

Mendoza, J (2011) ‘The Impact of Minority Stress on Gay Male Partner Abuse’ in Ristock, J. (2011) ‘Introduction: Intimate Partner Violence in LGBTQ Lives’. Routledge. Online Resource.

McKenry,P., Serovich, J., Mason, L. and Mosac, K. (2006) Perpetration of Gay and Lesbian Partner Violence: A Disempowerment Perspective, Journal of Family Violence (21).

Office for National Statistics (2017) Domestic abuse: findings from the Crime Survey for England and Wales: year ending March 2017 using statistics to tell us about victims and long-term trends. Last accessed 6 March 2020.

Office for National Statistic (2019) Sexual orientation, UK: 2017 Experimental statistics on sexual orientation in the UK in 2017 by region, sex, age, marital status, ethnicity and socio-economic classification. Last accessed 15 April 2020.

Peitzmeier, S. M., Hughto, J. M. W., Potter, J., Deutsch, M. B., & Reisner, S. L. (2019). Development of a Novel Tool to Assess Intimate Partner Violence against Transgender Individuals. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(11), 2376–2397.

Scottish Transgender Alliance (2013) Transgender People’s Experiences of Domestic Abuse. Accessed from Transgender People’s Experiences of Domestic Abuse. Last accessed 3 April 2020.

Stonewall (2018) LGBT in Britain: Home and Communities [online] Last accessed 3 April 2020.

Stonewall &NFP energy (2018) Supporting Trans women in domestic and sexual violence services. Last accessed 3 April 2020.

Tesch,B and Bekerian,B. (2015) Hidden in the Margins: A Qualitative

Examination of What Professionals in the Domestic Violence Field Know About Transgender Domestic Violence, Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 27(4).